Research is one of my favorite things about being an author, but sometimes it can become terrifying and overwhelming. This year, my latest novel, Lethal Agent, has immersed me in the world of viruses and pandemics. Expertise in this arena can be a bad thing—I now have way too much knowledge about how devastating a bioweapon could be.

I’ve been thinking about biological attacks since the 2003 SARS outbreak. My wife and I were embarking on an around-the-world trip at that time and I still remember brushing off our families’ demands that we cancel our trip. I felt a moment of regret when Singapore airport security tested us for fever, but we made it through without being quarantined. In the end, that trip produced nothing more dangerous than a bit of stomach upset from a sketchy zebra steak in Namibia.

Oakland Municipal Auditorium in use as a temporary hospital during the influenza pandemic of 1918. Photo: Edward A. Rogers

Disease Reshapes The World

The truth is that nothing in history—advancing technology, war, civil uprisings—has matched the sheer impact of disease. Plague wiped out nearly a third of 14th century Europeans, with casualties reaching as high as eighty percent in parts of southern France and Spain. It’s hard to fully grasp how much this changed the known world. To this day, we can see the effects of plague on politics, religion, art, and literature. Humanity’s relationship with death and its outlook on life were fundamentally transformed.

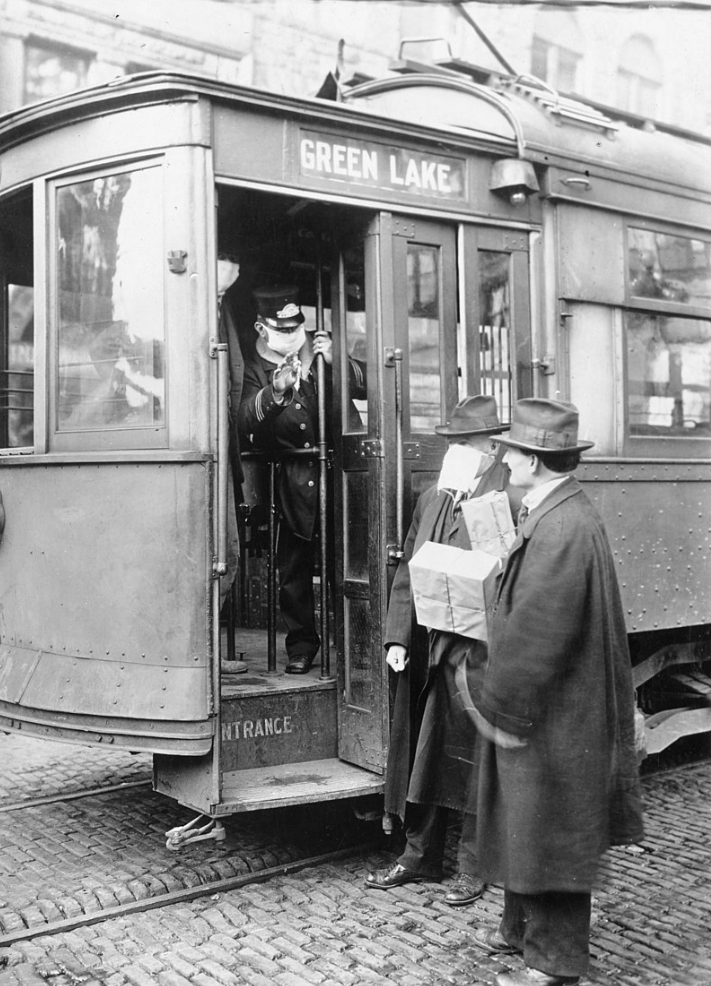

Street car conductor in Seattle not allowing passengers aboard without a mask.

The Spanish flu, which broke out around the end of World War I, killed about thirty million people worldwide. Extrapolated to the present day population, that disease would have taken the lives of 150 million.

Again, it’s hard for a citizen of the 21st century to imagine the scale of this pandemic. Surgical masks were worn in public. Stores were prohibited from having sales to prevent people from gathering in confined spaces. Some cities demanded that passengers’ health be certified before they boarded trains.

How bad was it? Bad enough for children to invent a nursery rhyme. Here’s what kids skipped rope to in 1918:

I had a little bird,

Its name was Enza.

I opened the window,

And in-flu-enza.

Pandemic In Modern Society

If a similar pandemic broke out in modern society the toll would be unimaginable. We live in an interconnected, heavily populated world. A disease that starts in Asia could be in the US, Europe, and Africa in a matter of hours. Medical services would be overwhelmed. International—and even interstate—commerce would stall as authorities tried to slow the spread of the disease. The machines that make our society possible—from food production and delivery to power generation and sanitation would break down as critical workers were incapacitated or died off. Bodies would go unburied and people would flee the cities. World economies would collapse.

But how likely is another pandemic similar to the ones of the past? Unfortunately, almost inevitable. Humans continue to move into unfamiliar habitat, bringing us into contact with animals and germs we haven’t encountered before. The massive demand for meat puts us in close proximity to livestock including pigs and birds suffering from infections that can jump species. The former scenario is probably the story of AIDS—a disease that started in chimpanzees and crossed over to humans. If that virus’s genetic code had been a bit different and it had gone airborne, today’s world would be very different place.

Bioweapons Aren’t Complicated

Finally, there’s my wheelhouse—terrorism. People tend to think of bioweapons as being engineered in some complex way, but it doesn’t have to be so. Lethal Agent is based on the terrifyingly plausible scenario that a SARS-like virus breaks out in Yemen. With no medical infrastructure to speak of and a war that prevents organized intervention like we saw in 2003, the disease is left to incubate in remote villages.

But how would someone weaponize it? Much has been written about crop dusters and other elaborate delivery strategies. But in reality none are necessary. Just smuggle a handful of sick people into a developed country. There you could have them loiter in airports, go to nightclubs, or get jobs in food service. The structure of modern society would do the rest.

These days, every time someone sneezes near me I think about 14th century Europe or the closing years of World War I. And, as usual, my newfound paranoia will haunt me until I replace it with the scenario for my next book…

*Image of the nurse on the Blog page: Walter Reed Hospital, Washington, D.C., during the great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 – 1919. Photo: Harris & Ewing Photographers